Given finite $A \subset \mathbb{Z}^2$, the harmonic measure of $x \in A$ is the probability that a simple random walk “from infinity” first visits $A$ at $x$. If $A$ has $n$ elements, what is the smallest positive harmonic measure that you can get?

Harmonic measure

Definition

Harmonic measure is defined in terms of simple random walk and its return times.

- Simple random walk $S_0, S_1, \dots$ in $\mathbb{Z}^2$ from $y \in \mathbb{Z}^2$ is the random process with $S_0 = y$ and increments $S_{t+1} - S_t$ which are i.i.d. uniformly distributed in the set $\\{e_1,-e_1,e_2,-e_2\\}$, where $e_1 = (1,0)$ and $e_2 = (0,1)$. Denote its distribution by $P_y$.

- For $A \subset \Z^2$, the return time to $A$, denoted $\tau_A$, is the first time $t \geq 1$ that $S_t \in A$.

This limit exists, so harmonic measure is well-defined.1

Importance

Harmonic measure is important because of its role in a class of interfacial growth models, known as Laplacian growth models. “Laplacian” is meant to indicate that each point along such an interface moves with a velocity or probability proportional to the gradient of a harmonic field, that is, a field that solves the Laplace equation. Because it can describe the motion of an interface in response to gradients in pressure, temperature, or an electric field, Laplacian growth is used to describe diverse natural phenomena including finger formation between viscous fluids,2 crystal growth,3 discharges in dielectric breakdown,4 vascular morphogenesis,5 the shape of river networks,6 and many others.

Some examples

How large can harmonic measure be?

$$ H_A (x) \leq \frac12.$$Here are two examples, which explain why this is true.

$$ H_A (x) = H_A (y) = \frac12.$$$$A_N = \\{x_{N,1},\dots,x_{N,n}\\},$$$$ H_{A_N} (x_{N,n}) \to \frac12.$$How small can harmonic measure be?

Since $H_A (x)$ is the probability that a random walk from infinity first hits $A$ at $x$, if $x$ is in the “interior” of $A$, then $H_A (x) = 0$. So we ask: If $A$ has $n$ elements, then what is the least positive value of $H_A(x)$? Here are two qualitatively different examples, which show that it can be exponentially small in $n$.

Example 2 (continued). The same reasoning we applied in Example 2 suggests that, if we “zoom into” $B_N$, then $x_{N,n-1}$ and the rest of $B_N$ look like two points and so evenly split the harmonic measure allotted to $B_N$ as $N \to \infty$. We can iterate this argument by subsequently zooming into the rest of $B_N$, and so on, until we ultimately conclude that $H_{A_N} (x_{N,1}) \to \frac{1}{2^n}$.

$$ A = \underbrace{\\{ (-1,j): 1 \leq j \leq L \\}}\_{\text{Left side}} \cup \\{ o,e_2 \\} \cup \underbrace{\\{ (1,j): 1 \leq j \leq L \\}}\_{\text{Right side}}.$$Here, the origin $o$ serves as the “base” of the tunnel, and $e_2$ is the element that we place at its “bottom.” Since any random walk from infinity which first hits $A$ at $e_2$ is forced to take the $L$ steps into the tunnel to reach it, this suggests that $H_A (e_2)$ is essentially $\frac{1}{2^L}$, which is exponentially small in $n$.

An interesting point is that both examples produce a value of harmonic measure which is exponentially small in $n$, despite being qualitatively different. Indeed, in Example 2, we produced a small harmonic measure by separating the elements at exponential scales while, in Example 3, we did so by forcing the random walk to take on the order of $n$ particular steps. This perhaps foreshadows the difficulty of proving a harmonic measure lower bound which is valid for every $n$-element subset of $\mathbb{Z}^2$.

A result from a recent paper

$$ H_A (x) \geq e^{-c n \log n}. $$$$ H_A (x) \geq e^{-c n}. $$Examples 2 and 3 show that, aside from identifying a better constant $c$, the lower bound for connected $A$ cannot be improved. In contrast, we do believe it should be possible to improve the first bound by removing the $\log n$ factor from the exponent. We formalize this as a conjecture, and even specify the set we suspect will realize the least positive value of harmonic measure (at least asymptotically in $n$).

A conjecture

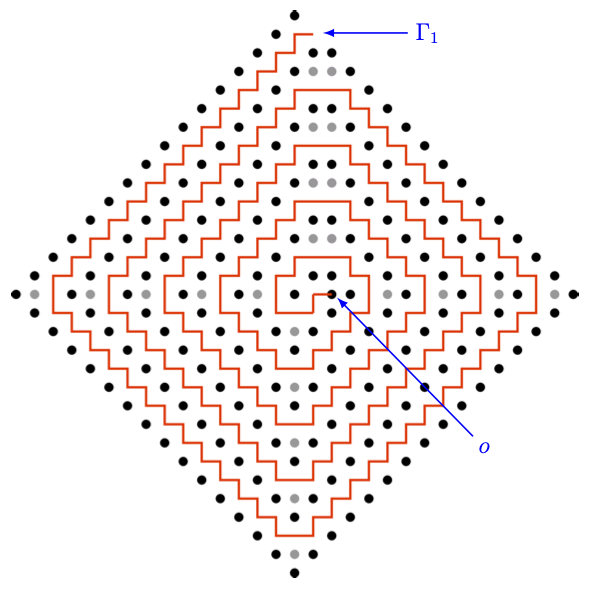

We conjecture that, given a sufficiently large budget of $n$ elements, the smallest positive value of harmonic measure is realized at the origin of a square spiral with $n$ elements (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A square spiral. The black and gray dots are elements of the set $A$, and the red line shows the path which a random walk is forced to follow if it is to first hit $A$ at the origin $o$.

In other words, $H_{A_n} (o)$ is approximately $e^{-cn}$, where $c = 2 \log (2+\sqrt{3})$.

The virtue of the square spiral is that a random walk from infinity which first hits $A_n$ at the origin must follow a particular path of roughly $2n$ steps (the red path in Figure 1). Compare this to the rectangular tunnel in Example 3, where the path to the bottom of the tunnel had a length of $\frac12 (n-2)$. I thank Joe Slote for this idea—of using a square spiral, as opposed to a spiral with “rounded” sides.

-

For example, see Chapter 2 of Lawler’s book: Gregory F. Lawler. Intersections of random walks. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Birkhäuser/Springer, New York, 2013. Reprint of the 1996 edition. ↩︎

-

Philip Geoffrey Saffman and Geoffrey Ingram Taylor. The penetration of a fluid into a porous medium or hele-shaw cell containing a more viscous liquid. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 245(1242):312–329, 1958. ↩︎

-

J. S. Langer and H. Müller-Krumbhaar. Theory of dendritic growth—I. elements of a stability analysis. Acta Metallurgica, 26(11):1681–1687, 1978. ↩︎

-

L. Niemeyer, L. Pietronero, and H. J. Wiesmann. Fractal dimension of dielectric breakdown. Phys. Rev. Lett., 52:1033–1036, Mar 1984. ↩︎

-

Vincent Fleury and Laurent Schwartz. Diffusion limited aggregation from shear stress as a simple model of vasculogenesis. Fractals, 7(01):33–39, 1999. ↩︎

-

Alexander P. Petroff, Olivier Devauchelle, Hansjörg Seybold, and Daniel H. Rothman. Bifurcation dynamics of natural drainage networks. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 371(2004):20120365, Dec 2013. ↩︎

-

Jacob Calvert, Shirshendu Ganguly, and Alan Hammond. Collapse and diffusion in harmonic activation and transport. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2110.13895.pdf, 10 2021. ↩︎